The Dreaded Jake-Leg and Prohibition (History Ctr Column)

In the United States from 1920 to 1933, a nationwide constitutional law, the Eighteenth Amendment, prohibited the manufacture, sale and transportation of intoxicating beverages. It did not outlaw the possession or consumption of alcohol. The Volstead Act, the federal law that provided for the enforcement of Prohibition, had enough loopholes and weaknesses to open the door to countless schemes to evade the “dry” mandate. Several of these schemes flourished in the backwoods, fields and even towns of Bossier Parish and northwest Louisiana. Reports in the local newspapers show that Bossier Parish law enforcement was kept busy tracking down the bootleggers (illegal manufacturers and distributors of alcoholic drink) and their hidden stills in the towns and remote corners of the parish.

Even when Prohibition ended, some parts of the area remained “dry” by local ordinance. In an oral history interview about living through the Great Depression, Gypsy Demaris Boston, who lived in Ida, a small town just across the Red River from the north Bossier town of Plain Dealing said, “the little town that I lived in, the ward was dry, that meant that we were not allowed to sell whiskey, but you could just go five or six miles west and that ward would sell whiskey, but five or six miles was too far for many of the people to get their whiskey so there were bootleg stills around Ida and a few of them made the wrong kind of whiskey and a few people took Jake Leg disease from drinking alcohol – which was a wood alcohol and a poison - rather than the alcohol that people usually drink to get drunk on.”

Ms. Gypsy, who passed away in January, 2022, at the age of 102, brought up an unintended and tragic consequence of Prohibition, beyond the Hollywoodized stories of outlaw bootleggers and the cat and mouse games to catch them. The “bootleg” system meant people were consuming something that was completely unregulated, and it could cause a serious neurological syndrome that, until my interview with Ms. Gypsy, I had not heard of: “Jake-Leg”.

“Jake” was an abbreviated name for a common patent medicine, Jamaican Ginger. Because of their high-alcohol content, patent medicines were often consumed by folks to fulfil their craving for alcohol. Jamaican Ginger had an especially high alcohol content, 70-80 percent. To prevent this work-around for buying and selling alcohol during Prohibition, the Federal government required the non-prescription version to have a high content of bitter-tasting ginger oleoresin to give it an unpalatable taste and classify it as “nonpotable.”

Manufacturers were always looking for cheaper additives that also tasted less bitter but would still allow them to pass the government’s Prohibition audits. One manufacturer of Jamaican ginger, Boston-Hub company, eventually chose a mixture containing TOCP, a plasticizer used in lacquers. The TOCP manufacturer, the Celluloid Corporation, claimed that it was non-toxic. However, it was later determined to be a neurotoxin that especially causes damage to the nerves in the spinal cord.

The first cases of Jake users reporting to doctors that they were unable to use their hands and feet were in Oklahoma City, OK in 1930. Some could walk, but they had no control over the muscles that allowed them to point their toes upward. Therefore, they would raise their feet high with their toes flopping downward, making their toes hit the ground first, followed by their heels. This very distinctive gait became known as the “jake walk” or the “jake dance.” Additionally, the calves of the legs would loosen and sag and the muscles between the thumbs and fingers would atrophy, among other unpleasant or disabling symptoms. There was no cure; some sufferers would improve over time, others would not.

As Ms. Gypsy’s commentary shows, neurological effects of bootleg alcohol, also known as “moonshine,” were sometimes also referred to as “jake-leg.” Sometimes these symptoms were the effects of lead absorbed from improper stills (such as ones made with old radiators) or containing improperly soldered connections which could cause lead poisoning, partial paralysis or “jake-leg” type symptoms.

Some accounts contemporary to the era put the blame for their affliction squarely on the sufferers of Jake Leg, such as “Col. I.B. Dearne” who wrote a syndicated column, “The Dearne Dope” that appeared in the Jun 5th, 1930, Bossier Banner Progress stating that both jake leg and the economic depression of the time were all consequences of excess. “We’ve got everything we have ever had in this great country, and lots of things we never had before, including jake leg and swell head, to say nothing of homes full of installment furniture.”

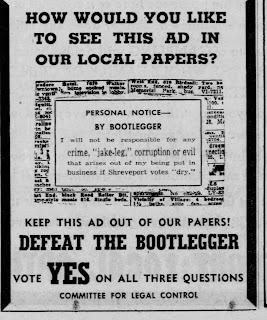

However, by the 1950’s when further local measures prohibiting alcohol were being considered, the prospect of jake leg was used as a reminder of the unintended negative consequences of taking regulation away from something humans seemed determined to consume. “The Shreveport Journal” of Jul 15th, 1952 published a notice from “The Committee for Legal Control” that was made to look like an enlarged classified ad, and asked, “How would you like to see this ad in our local papers? ‘Personal Notice by Bootlegger: I will not be responsible for any crime, “jake-leg, “corruption or evil that arises out of my being put in business if Shreveport votes dry.’”

A group of citizens published a letter in an advertisement in the June 5th, 1952, “Bossier City Planters Press” to support two business owners who apparently sold liquor and were the subject of a pamphlet questioning their morals by reminding readers, “We lived through one Prohibition…We have seen running gun battles on Milam Street [in downtown Shreveport], minors crippled from the ‘Jake Leg,’ bootleggers and politicians working hand in hand.” The letter stated these business owners were “respectable citizens of Bossier City, property owners, taxpayers, church-goers, and civic minded gentlemen” … with customers who “are respectable, intelligent adults who enjoy a drink from time to time.”

If you’d like to know more about Prohibition you can watch episodes of the Ken Burns documentary series “Prohibition” which is available to stream for free with your library card through Kanopy. If you need help accessing Kanopy, contact or visit us at the Bossier Parish Libraries History Center. You can also visit or contact us to peruse our oral history collection, and read the transcript of interviews such as Ms. Gypsy Boston’s. We are located at 2206 Beckett Street, Bossier City. We are open: M-Th 9-8, Fri 9-6, and Sat 9-5. For more information, and for other intriguing facts, photos, and videos of Bossier Parish history, be sure to follow us @BPLHistoryCenter on FB, @bplhistorycenter on TikTok.